Cell regeneration has long been seen as something out of science fiction. For generations, salamanders have been able to regrow entire limbs, while humans can barely regenerate the very tips of our fingers — and only in limited circumstances.

Yet a growing body of research suggests the story of human regeneration is far from finished. This new understanding of cell regeneration is redefining what may be possible. Scientists are uncovering the biological rules that govern how tissues rebuild, why certain parts of the body can regenerate while others cannot, and what signals might “unlock” dormant healing potential.

A new study offers one of the clearest breakthroughs yet. Researchers have identified a single developmental protein, FGF8, that can regrow an entire joint in a setting that normally produces only scar tissue. And while the work was done in neonate mice, its implications reach much further: toward the future of regenerative medicine, limb renewal, and next-generation biologics.

Understanding how cell regeneration works helps explain why some tissues heal fully while others cannot. Let’s explore what this landmark discovery means.

What Is Cell Regeneration?

Cell regeneration is the body’s natural ability to replace damaged or lost tissues. Some tissues regenerate exceptionally well — like skin, the gut lining, blood, and bone. Others regenerate poorly or not at all.

In mammals, the list of parts of the body that can regenerate is short compared to highly regenerative species. Humans can naturally regenerate:

- skin

- blood cells

- the liver (up to a point)

- bone (with limitations)

- fingertips in very young children

But mammals rarely regenerate complex structures like joints, ligaments, or full limbs. Instead, these tissues tend to repair through scarring; a quick fix, but one that sacrifices original structure and function.

This is why researchers are exploring what regenerative medicine is used for: to help restore tissues the body cannot rebuild on its own.

Why Joint Regeneration Is So Challenging

Joint tissues, especially articular cartilage, don’t regenerate well. Cartilage has:

- Minimal if any blood supply

- limited cellular turnover (due to having very few cells)

- very low metabolic activity

Once damaged, cartilage typically stays damaged. This is one of the clearest examples of where cell regeneration is extremely limited in mammals. This is why osteoarthritis progresses over time, and why athletes with cartilage injuries often face chronic discomfort.

So the question researchers have been chasing is simple: Can humans regenerate joint cartilage?

Outside of some very specific regenerative joint restoration procedures, until recently, the answer was “not really.” That’s what makes the FGF8 study so remarkable.

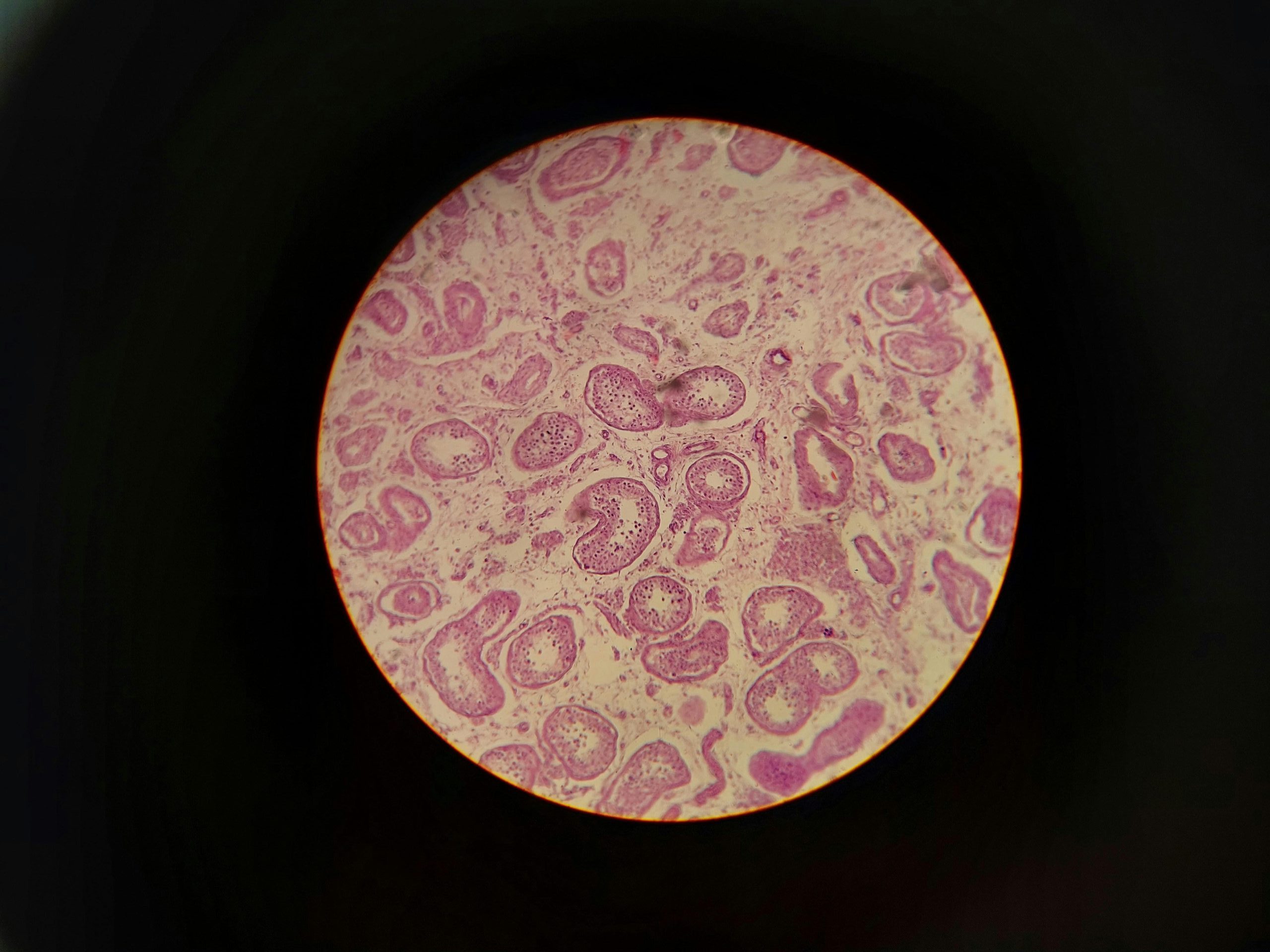

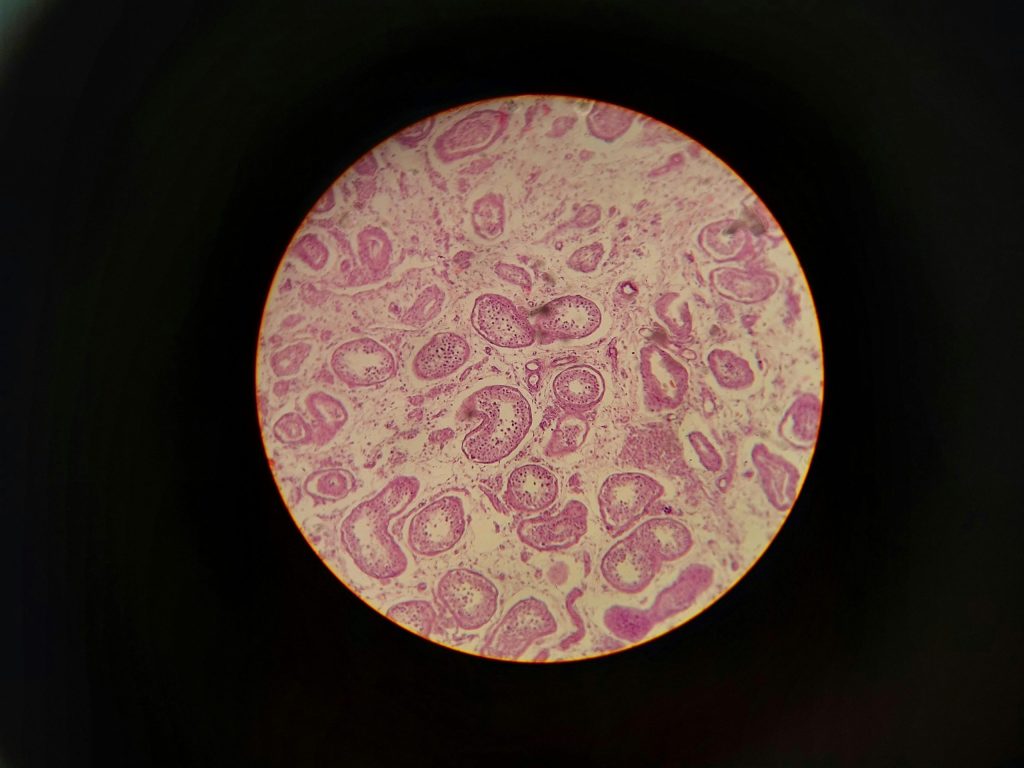

The Breakthrough: FGF8 Can Regrow an Entire Joint

In a groundbreaking study, researchers implanted different fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) into mouse digit amputations to see if any could trigger regeneration.

Only FGF8 did.

Amputations at the P2 (middle) segment of the digit in mammals normally heal with:

- bone truncation

- scar tissue

- no regrowth of joint structures

But with FGF8, something extraordinary happened. The treated tissues regenerated:

- a synovial cavity (the hallmark of a functional joint)

- articular cartilage

- tendon

- ligament

- a cartilage “template” that partially restored bone

- early fingertip structures

This is known as composite regeneration — the body rebuilding multiple, highly specialized tissues together as a unified unit.

As Dr. Lindsay Dawson explained:

“These cells would normally undergo scar formation, but FGF8 tells them to do something else — and they end up making five tissues. We were amazed at how much this one factor can do.”

FGF8 appears to “speak the language of development,” reactivating programs normally used only during embryonic limb formation. By reawakening these pathways, it may activate forms of cell regeneration that are normally dormant.

Why This Matters: The Body Has Dormant Regenerative Capacity

This discovery echoes a central concept across regeneration research: mammals can regenerate more than we think, the instructions are just turned off.

The Poss review (Nature Reviews Genetics) highlights that highly regenerative species keep developmental signals active throughout life, whereas mammals silence them after birth. But these pathways still exist. They can be reawakened under the right conditions.

FGF8 appears to be one such trigger.

This study demonstrates a critical principle: The capacity for regeneration is not absent — it is dormant. FGF8 reveals how targeted signals can help unlock deeper levels of cell regeneration.

And if you can regenerate a joint, you’re no longer talking about minor tissue repair. You’re talking about rebuilding structures and functions.

A Step Toward Regrowing Limbs?

Dr. Dawson’s team approaches this work with a bold vision:

“If we can figure out all the factors that regenerate a finger, then we could apply those factors anywhere on the rest of the arm, or even a leg, and regrow a limb.”

FGF8 alone cannot rebuild a full limb, but it proves something once thought impossible: a non-regenerative wound can be converted into a regenerative one.

This opens the door to further exploring:

- combinations of growth factors like FGF8

- exosome-based signaling

- gene-regulated repair

- precision biologics that guide cells, rather than replace them

And it aligns directly with the future of regenerative medicine: helping the body heal not by force, but by reminding it how. By understanding and directing cell regeneration more precisely, researchers may one day guide the body toward true structural renewal.

Examples of Regeneration in the Natural World

To appreciate the significance of this work, it helps to look at animals that do regenerate:

- Axolotls regrow complete limbs.

- Zebrafish regenerate fins, spinal cord, and even parts of the heart.

- Planarians regenerate entire bodies from tiny fragments.

Their secret? They keep developmental pathways — including FGF, Wnt, and BMP signaling — active throughout life. Humans switch them off.

FGF8 may be one key that reopens that locked door. These species show what is possible when cell regeneration remains active throughout life — a contrast that highlights the significance of the new FGF8 findings.

Can Humans Regenerate?

In limited ways, yes. And usually with help through regenerative medicine. Most human tissues rely on repair rather than true cell regeneration, which is why breakthroughs like FGF8 are so important.

This research shows that with the right signals, that capacity may be far greater than we assumed, especially if we can learn to guide adult tissues the way embryonic tissues respond to developmental cues.

It’s early work, but meaningful.

And it reinforces a powerful truth: Regeneration isn’t science fiction. It’s biology waiting to be understood.

Where Science Meets Renewal

At ReCELLebrate, we believe the future of healing lies in precision-guided cellular renewal — not forcing change, but activating the deep intelligence already written into our biology. Already a pioneer in cartilage regeneration and helping in reversing osteoarthritis to help avoid surgery, Dr. Gross is expanding his efforts into accelerating joint and limb regeneration with advances in cell signalling, like FGF8.

If you’re ready to explore what’s possible for your long-term cellular health, joint or limb regeneration, or other cutting edge biomedicine, our use biologics offer a grounded and supportive place to begin.

Your cells remember how to renew. Breakthroughs like FGF8 continue to expand our understanding of cell regeneration and its future potential.

Connect with us today to learn more about your regenerative medicine options.

References

- Yu L, Yan M, Wolff SM, Knue JD, Smith HM, Dolan CP, Muneoka K, Romero S, Cai JJ, Yun C, Boland DJ, Brunauer R, Dawson LA. FGF8 induces bone and joint regeneration at digit amputation wounds in neonate mice. Bone. 2026 Jan;202:117663. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2025.117663. Epub 2025 Oct 3. PMID: 41046114.

- Researchers uncover key element of joint cartilage regrowth. Texas A&M University, College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences.

- Poss, K.D. Advances in understanding tissue regenerative capacity and mechanisms in animals. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2010.